READ MORE ABOUT

123 Proven Ways to Reduce Stress and Relax

https://healthgrinder.com/ways-to-reduce-stress/

The most maddening—and the most common—response I get when I write about the daughters and sons of unloving mothers is that people point out that the ones I write about were “only” (quotations marks mine, and meant ironically) verbally abused. Science knows better, but the culture does not; the mantra seems to be that if you’re not bleeding or physically maimed, you’re not really hurt.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Why is it that, as a culture, we’re so resistant to acknowledging the impact of verbal aggression? It’s taken much effort to convince people that the bully in the schoolyard isn’t a “normal” part of growing up. There’s still considerable ambivalence about acknowledging that “normal” sibling rivalry can become bullying in the living room. Ditto on domestic abuse which often requires evidence of physical trauma to be believed as genuinely damaging. Consider that the report from the American Academy of Pediatrics which sought to define psychological maltreatment of children was issued a mere 14 years ago. Their definition is useful to keep in mind: “Psychological maltreatment of children occurs when a person conveys to a child that he or she is worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered, or only of value in meeting another’s needs.”

Is it surprising many daughters of unloving mothers remark that they wish they’d been beaten so that their scars would show—and people would believe them?

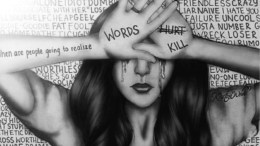

Words are powerful: They can lift us up and beat us down, soothe us or wound us. Here’s a brief run-down of what science knows about verbal aggression and which you should too, especially if you’re a parent or just a member of the human race. Verbal aggression and abuse can be part of an intimate relationship or friendship but it also shows up in the workplace and elsewhere for adults, and many more places for children. Here’s the science of why you and I should not ignore it.

1. The circuitry for physical and emotional pain appears to be the same.

Neuroimaging in a series of experiments conducted by Naomi L. Eisenberger and others showed that the same circuitry associated with the affective component of physical pain was activated when participants felt socially excluded.

But another experiment by Ethan Kross and others went further, testing if they could involve the parts of the brain that are involved with both the affective and sensory components of physical pain. They recruited 40 people who had experienced an unwanted and hurtful romantic breakup. Using MRI scanning, they asked participants to look at a photo of their ex and specifically think about how they felt rejected. Then they had the participants look at a photo of a friend who was the same gender as their ex and think about positive experiences they’d enjoyed with that person. Pain tests were also administered to the participants: one a “hot trial” that actually hurt and one a “warm” trial that had enough heat to cause sensation but not discomfort.

The result? The same parts of the brain lit up when the lost love and rejection were recalled as when the hot trial was applied to the forearm. This is an avenue to be further explored by science but it would appear that emotional and physical pain are very much the same. Listen up: “Heartbroken” may not be a metaphor.

2. Verbal aggression literally changes the structure of a child’s developing brain.

Yes, that’s what the work of Martin Teicher and his colleagues discovered, and it’s very scary indeed. We can “thank” evolution for this adaptability (yes, that’s irony) since the brain goes into survival mode, retooling so as to deal with an environment full of stressand deprivation. It will not surprise you that these effects are lasting. Other studies have identified the areas of the brain most affected as the corpus callosum (responsible for transferring motor, sensory, and cognitive information between the two brain hemispheres), the hippocampus (part of the limbic system which regulates emotions), and the frontal cortex (thought and decision-making). Another study, conducted by Akemi Tomodo and others, showed correlation between verbal abuse and changes to the gray matter of the brain, without proving causation. Nonetheless, the direct effect verbal aggression has on the child’s brain appears to be beyond dispute.

Parents: Just think about the effects of your words, would you?

3. The effect of verbal aggression is greater than the expression of love.

One group of researchers wondered whether the presence of a reasonably attentive and affectionate parent could offset the damage done by a verbally aggressive one and discovered that, alas, it couldn’t. In fact, the effects of parental verbal aggression and parental verbal affection seem to operate independently of each other; additionally, while verbal affection on its own appeared to support healthy development, it didn’t appear to offer any buffer against the ill effects of verbal aggression. So—and feel free to switch up mother and father here—if the mother is affectionate and the father is the verbal abuser from hell, Mom’s kindnesses aren’t going to mitigate the damage done by Dad one bit. That is sobering, to be sure. Additionally, should the offending parent then demonstrate verbal affection, that too didn’t lessen the effect of the verbal aggression. This seems particularly relevant to the quandary of children whose mothers demonstrate behaviors that swing unreliably from one end of the spectrum to the other—cold, distant, or verbally abusive, one moment, and smothering the child, being overly effusive and intrusive. the next. Neither extreme fills the child’s needs for attunement since neither has anything to do with his or her needs; it’s all about Mom. These children have an ambivalent/anxious attachment style because they never know whether the Good Mommy or the Bad Mommy will show up. This study suggests, of course, that it’s the presence of the Bad Mommy that influences the child’s development most and lastingly.

4. Deliberately inflicted emotional and physical pain hurt more.

At a glance, there’s nothing counterintuitive about this statement—of course, your response will be different when someone trips you by accident and you skin your knees than it will be when someone deliberately tackles and takes you down—but it turns out that our perception of someone’s motivation literally affects how much physical pain we feel. Now, that is noteworthy. And it’s what Kurt Gray and Daniel Wegner discovered in an experiment which had participants work in pairs; one member (called the “confederate”) would be administering tests and the other receiving. Three of the tasks were benign but the final one involved the delivery of an electric shock which would have to be rated on a scale from “not uncomfortable” to “extremely uncomfortable.” In one group, the confederate was told to choose the shock when it was a possible choice; in the other, the confederate was told to avoid the shock. The participant was informed that that unbeknownst to the confederate who was told to avoid the shock, the signals had been switched and the shock delivered despite the confederate’s intentions.

The upshot? Even though the electric shocks were uniform, intended pain was perceived as being more painful. Words said with malice, intended to hurt or disparage, deliver more of a wallop than those said without forethought or true intention. If you put verbal abuse on a daily schedule—reliable and unwavering—it is that more painful and, yes, more damaging. Ask any verbally disparaged child.

5. Verbal aggression and abuse are internalized.

I know this both from personal experience and from the many hundreds of stories shared with me by unloved daughters and sons over the years that stilling the shaming, dismissive, or hypercritical maternal voice in your head is one of the most difficult parts of healing. Not surprisingly, science backs up the observation not just pointing to the association between parental verbal abuse and anxiety and depression over the lifespan, but with “self-criticism.” What is self-criticism? It’s the mental habit of attributing all bad things that happen to you to global, stable, internal factors, many of which may echo your mother or father’s words such as “I failed because I am stupid and incompetent” or “Nothing good will ever happen to because I’m not good enough” or “I deserve bad things because there’s nothing good about me.”

So, if you’re still wondering whether verbal abuse is “real” or has “real” effects, it’s time to stop kidding yourself and pay to attention to not just what you say but why you are saying it and to whom. I am emphasizing the vulnerability of children for a reason but keep in mind that adults often have their own fragilities as well.

SOURCE:https://www.psychologytoday.com